When did you arrive and where are you currently working?

I arrived in early April and am based in the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) countrywide co-ordination office in Sana’a, the largest city in Yemen, but I have spent most of my time in the field on projects in Ad Dhale, Houdaydah and Taiz. None of these cities are that far apart, but due to the numerous checkpoints and mountain passes, travelling 250km can take seven hours.

Can you give us an account of how you felt in your first week?

I honestly don’t remember, but I know I am certainly now used to frequently hearing air strikes and shelling events. The biggest change has been the increase in the number of injured civilians during my stay. At halfway through 2017, Yemen had already experienced more air strikes than in the whole of 2016.

What kind of cases are you dealing with?

Cholera and trauma are my immediate answers. MSF teams certainly treat a lot of trauma cases — adults and children, civilians and combatants. These include many war wounded and victims of road traffic accidents. The care encompasses ED stabilisation to operating room, and inpatient wards, including high dependency and ICU level care. We also treat many common health problems as there are limited other options for free, accessible, high-quality care.

One of our projects is focused on maternity and child health and we are overwhelmed with the high need for neonatal care beds and support for complicated deliveries.

The number of preterm deliveries is increasing, with younger mothers and increased malnutrition and stress all contributing factors.

What experiences have had the biggest emotional effect on you?

There are really hundreds to reflect on, none more important than any other. I do remember the eight-year-old girl whose arm was blown off in a bus explosion, where more than 20 civilians were injured, and the rush to get her to the operating theatre to properly control the bleeding. I also remember the device that exploded under another civilian bus, but was allegedly planted to hit an ‘important leader’ of one of the warring parties.

The physical injuries are gruelling and visible and yet the impact on mental health is unfathomable.

The strength of the MSF local staff is awe-inspiring. Their lives have been turned upside down. These are the individuals who tell me that the local library or store was hit in the latest air strike.

They have lost numerous family members and left their homes, which are now looted and overrun.They occasionally tell me of the struggles they must endure to get to work, as the road is blocked or unsafe. While I tell them to stay home, they arrive ‘better late than never’. They keep on going. They are the real humanitarians here, and we are lucky to have their skills and dedication to keep our MSF operations running to support the population in need.

People say we live in troubled times, but the war in Yemen has been called the ‘forgotten war’ by Amnesty International.

As I have been living and working in Yemen for the past six months, it’s hard to imagine how this is the ‘forgotten war’, but I understand it’s a situation where it can be hard to fully comprehend what’s going on.

The civilians are paying an extremely high price in this conflict. They live under the constant threat and reality of violence, fear and displacement, while trying to afford everyday commodities in the face of increasing prices and job insecurity.

We need the international community to step up and address the crisis in Yemen, not only by stepping up humanitarian solutions, but by addressing the factors that create such enormous humanitarian needs.

What protective measures are you taking against cholera?

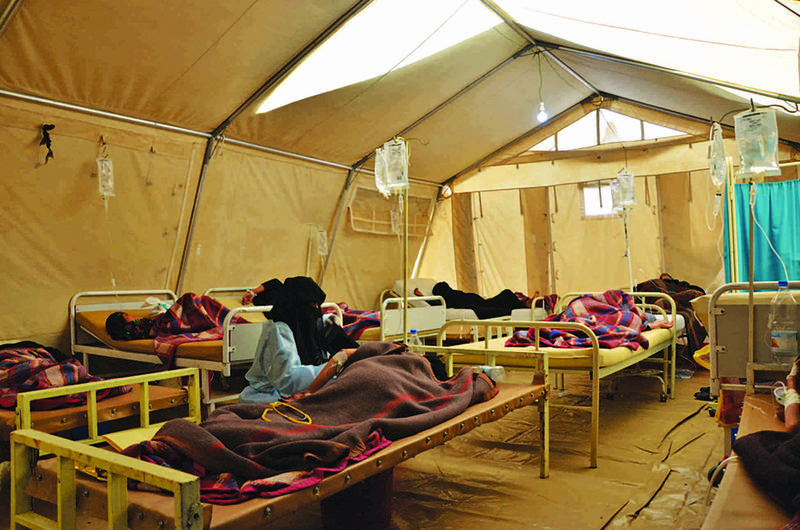

MSF has been largely focused on cholera case management. This was a pragmatic decision at the beginning of a rapidly increasing outbreak. When we initially looked at response capacity in Yemen, we knew other agencies were able and willing to do community prevention activities, but very few could rapidly set up and manage cholera treatment centres at the scale and speed required.

Essentially, MSF and two other organisations took on this role across Yemen. Of course, MSF has also had some involvement in prevention, but the largest effort has been on case management and rehydrating those with diarrhoea — simple treatments save lives. MSF outreach teams have joined Yemeni Ministry of Health community surveillance teams to investigate reports of community deaths, undertake contact tracing, and to provide health education and home water chlorination supplies and advice.

There are effective oral cholera vaccines for outbreak control, but timing is crucial to their effectiveness. The availability, more so than cost, is the major hurdle to implementation. A risk assessment was done in Yemen, but the availability in terms of acceptability, time frame and quantity were major barriers to the projected effectiveness of such a campaign.

Discussions on a country and international level are currently focused on a prevention campaign for 2018, given that cholera is endemic in Yemen.

Is there any access to clean water and sanitation for the people affected? They must be living in tremendous fear.

Hygienic waste management is problematic across Yemen with the breakdown of government services linked to no payment of civil servants for over one year, but the individual risk is largely determined by location. As Yemen is a middle-income country, the situation varies according to the living conditions.

In major cities, the reticulated water system could be treated by mass chlorination, that is, once the outbreak was detected. This is not possible for families living in remote villages who rely on well or open source water. Wells can be chlorinated, but the response time is slower due to remote access. A focus on household hygiene is an effective and simple protection measure.

How are the bodies of the dead disposed?

Our advice is about the safe and dignified handling of dead bodies, especially if cholera is the suspected cause of death although, thankfully, the death rates have been low in this epidemic.

In the Islamic faith, bodies are buried within 24 hours and washed prior to burial, so we have home hygiene kits and provide clear instructions on how to ensure a body is safely buried in a dignified way.

Did you ever think you would be confronted with a cholera outbreak?

Cholera is endemic in Yemen and there are permanent diarrhoea treatment centres set up across the country for just this reason.

Did anyone expect an outbreak of over 700,000 suspected cases in less than six months? Well, no, but the contributing factors of conflict, lack of access to healthcare and no payment for Ministry of Health staff for over a year obviously contributed to the deterioration of the health system, waste management and sanitation services.

How long will you stay in Yemen?

I will complete six and a half months in Yemen and then hand over to my replacement. It is honestly exhausting.

New challenges arise every day in terms of the response, patient care and rotating international staff, but the emphasis is on providing the very best MSF support — both to our patients and our Yemeni colleagues, who just keep going.

What is happening to the Yemeni health workers?

Tens of thousands of Yemeni health professionals remain dedicated to providing care in public health facilities despite not having received their salaries for more than one year.

How long do we expect them to continue as volunteers? What options do they have other than to move to the private sector in order to survive and provide for their families? Once in the private sector, they may never come back.

International aid organisations, donor governments and all parties to the conflict must ensure that aid is delivered to those in need via activities on the ground that have meaningful impact, including direct support to those who administer the supplies. Many other agencies are not able or willing to provide salaries as a form of support.

Additionally, support is more than just the delivery of supplies, as we all know that having supplies does not ensure patients receive the correct treatment.Working in Yemen is not for everyone, and donations from every corner of the world keep us going. I work with MSF because we ensure a ‘chain of care’, as quality care requires staffing, supervision and training, supplies and referral options.

Note that this article was initially published in Australian Doctor.