Umberto Pellecchia, an anthropologist working with Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF), conducted in-depth interviews with inmates at Malawi’s Maula prison.

The men are squeezed together on the cement floor, with a space of less than half a square metre per person on average. The worst is at night. The heat emanating from dozens upon dozens of bodies is so stifling it’s palpable.

Packed tightly like battery hens for 15 hours a day, the inmates sit up in rows, their heads lolling on their knees, occasionally rolling onto a neighbour’s shoulder.

Undocumented migrants

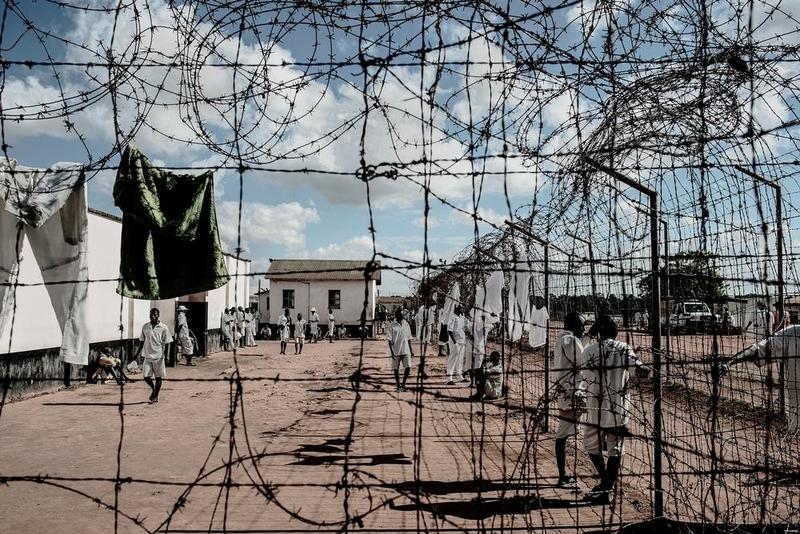

This is the harsh reality of overcrowding in Maula prison, in the Malawi capital of Lilongwe.

Built to accommodate 800 prisoners, Maula is bursting at the seams with 2,650 inmates. Amongst this desperate population, the most vulnerable are the nearly 300 undocumented migrants who were arrested as they travelled towards South Africa.

Seeking refuge

These men represent the reality of our mobile world, where people are on the move, seeking refuge from violence and inequality or escape from chronic poverty.

Lacking any kind of resources, they left their countries of origin in the hope of building a decent life in South Africa. A dream denied at home, that dramatically ended up in Malawi’s prisons.

It is a bright June morning when I visit Maula prison to assess the living conditions of foreigners who have been deemed by the court as undocumented migrants.

"We are not criminals! But now, in prison, we are not human anymore."

The sun shines a bleak light on the daily realities of migrants held together with common-law offenders, some of whom are serving long sentences for violent crimes.

'We are 204 in this cell,' says Thomas, a Malawian inmate, pointing to the number written on a blackboard in the 60 square-metre cell. He introduces me to a group of young Ethiopians sitting outside in the sun.

'It gives us Vitamin D,' jokes Abeba, a man in his thirties from Durame, Ethiopia. 'We are not criminals! But now, in prison, we are not human anymore,' he says.

Humanitarian concern

The number of foreign citizens, mostly Ethiopians, detained in Malawi for illegal entry has increased in the past few years, and has become a phenomenon of humanitarian concern.

Most have been charged for three months, but the reality is that they have been locked away for more. The law requires they return to their homelands after their periods of detention, but bureaucratic delays impede any way forward.

Moreover, they are supposed to cover their expenses for repatriation, a contradiction to their weak economic status.

A young boy leaning on a wall tells me, 'My dream is to reach South Africa; this is what I have worked towards for years. I knew it would be difficult, but I never thought I’d end up here.

'I thought Africans were all brothers. But here…here it seems different.' He stares at me, as if questioning for the first time what he had always thought to be true.

One meal a day

Three young men are grading beans outside their cell. 'You see? These are not good. They are uncooked and rotten,' says one of the men. 'We eat them like that,' another inmate adds.

Prisoners in Maula get food only once a day. They usually eat a plate of nsima – ground maize that fills the stomach but doesn’t give many nutrients. Beans are an occasional treat. Nutrition is so poor that last month MSF had to treat 18 inmates for moderate-to-severe malnutrition.

Last hope for survival

Ethiopians follow a long-standing pattern of migration towards South Africa, their beacon of light.

'Where we live, there is not enough land for everyone, we are too many in my family,' says Abeba, counting with the fingers on both hands the number of brothers in his family.

'If I go to South Africa, after two or three years I can afford to buy a house. If you work for 20 years in Ethiopia you can’t buy anything,' he says. Another young Ethiopian adds, 'If you need a job there, you have to belong to a certain family that has land. My family doesn’t have any.'

For many, leaving the country wasn’t a choice. It was their last hope for survival.

Can't go back

Emmanuel pulls out his torn wallet, opens it and shows me the transparent sleeve inside. Instead of pictures, it holds his talisman: a piece of paper with three phone numbers on it.

'These are my friends in South Africa,' he says. In the courtyard of the prison, Abeba gazes at the other inmates playing football. I ask him if he wants to go back to his country. He turns his head towards me, with a serious smile too mature for his age.

'We can’t go back,' he says. 'If we go back to Ethiopia, what could we do there? We can’t work anymore. We have become too sick for any kind of work.'"